In late 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led their expedition north along the mighty Mississippi River, traveling from the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers near present-day Cairo, Illinois, to their winter encampment at Camp Dubois, near modern-day Wood River, Illinois. This route, which took several weeks, was a vital preparation for their legendary journey west. Follow in their wake and explore the significant stops along the way—where history was made and the adventure truly began!

Note we have parallel trips on the east and west banks of the Mississippi River section of the Expedition. For the Illinois side of the river Trip. For Around St. Louis.

Check our Events page for even more things to do while on this journey and read more about this section of the Expedition in our Digital Travel Magazine library.

You may also like our L&C Travel Magazine!

After arriving at Cape Girardeau on November 23, 1803, Lewis took letters of introduction to Louis Lorimier, whose store in Ohio was burned to the ground by William Clark‘s brother—George Rogers Clark—in 1782. Lewis picked Lorimier’s brain for information about what lay ahead.

The Red House Interpretive Center is located just off Main Street in historic downtown Cape Girardeau. The Center commemorates the life of community founder and French-Canadian, Louis Lorimier, as well as the visit of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in November 1803. The Red House Interpretive Center houses an early 1800s exhibit that reflects the lives of the early settlers of the old Cape Girardeau district. In addition, a rendering of Lorimier’s Trading Post displays authentic items that would have been sold at the turn of the 19th century.

Mississippi River Tales Mural, North Water Street, Cape Girardeau, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Red House Interpretive Center, Aquamsi Street, Cape Girardeau, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

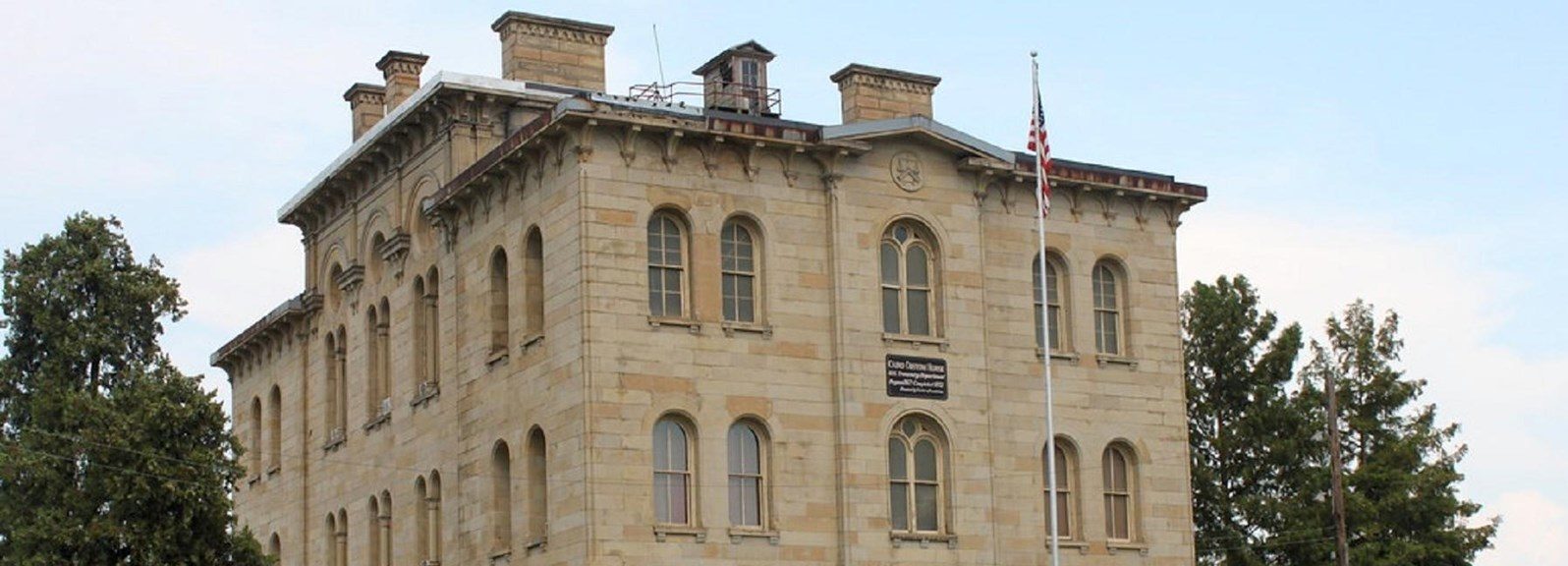

Cairo Custom House Museum, Washington Avenue, Cairo, IL, USA

28 mi

View Listing

After an early start on November 24, 1803, Sgt. Pryor, a Corps of Discovery hunter who had been lost the past two days, was found. As they worked their way ten miles up the Mississippi, Lewis observed the limestone lining the shores and hills of present Trail of Tears (Missouri) State Park.

The park’s name honors the forced removal of the Cherokee people between 1838 and 1839. Following the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 and the controversial Treaty of New Echota in 1835, over 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly relocated to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). While some detachments traveled by steamboat, most endured a grueling overland route, crossing the Mississippi River at what is now the park. Today, Moccasin Springs Road, located in front of the Visitor Center, remains a visible part of the original trail.

Trail of Tears State Park, Moccasin Springs Road, Jackson, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

On November 25, 1803, Lewis wrote, “Arrived at the Grand Tower a little before sunset, passed above it and came too on the Lard. [left] shore for the night.” In 1673 French explorers Père Marquette and Louis Joliet listened to local Indians’ warnings about this place and erected a cross atop the ninety-foot-high rock to disempower the demons said to be lurking in the treacherous whirlpool at its base. Lewis explained: “This seems among the watermen of the Mississippi to be what the . . . Equinoxial line is with regard to the Sailors; those who have never passed it before are always compelled to pay or furnish some sperits to drink or be ducked.”

In fact, the river around the Grand Tower can be devilishly dangerous, as Lewis was told: “When the river is high the courent setts in with great violence . . . this courent meets the other portion of the river which runs E. of the Tower. . .; these strong courants thus meeting each other form an immence and dangerous whirlpool which no boat dare approach. . .; the counter courent driving with grat force against the E. side of the rock would instantly dash them to attoms and the whirlpool would as quickly take them to the bottom.” Lewis was informed that “in the present state of the water there is no danger in approaching it.” Indeed, every few years, when the water is low it is possible to walk to the Grand Tower or Tower Rock on dry sand, but when the Mississippi is high, even modern towboat pilots shy away from it.

After the Civil War, when the Corps of Engineers intensified channelization work on the Mississippi, clearing rocks, shoals, snags and other impediments to safeguard river commerce, Tower Rock was left standing as a footing for a proposed railroad bridge. The bridge was never built and Tower Rock is now a National Historic Site.

Villainous Grounds, North Jackson Street, Perryville, MO, USA

20 mi

View Listing

Mary Jane Burgers & Brew, North Jackson Street, Perryville, MO, USA

20 mi

View Listing

On November 27, 1803, Lewis and Clark camped near what was then the lower portion of Horse Island, located just below the mouth of the Kaskaskia River at a sharp bend in the Mississippi. Over time, the shifting river course has resulted in Horse Island being absorbed into the Missouri shoreline, while the Mississippi moved eastward, erasing the original village of Kaskaskia. What replaced it is nonetheless historic.

A roadside historical marker on the site of Horse Island offers visitors a chance to connect with the past and gain insight into the landscape as it appeared in 1803. When the expedition reached Horse Island, Captain Meriwether Lewis disembarked to walk the six-mile journey to Fort Kaskaskia, an American Army post located on high ground east of the Kaskaskia River, opposite the village. Meanwhile, William Clark remained in charge of the keelboat and pirogues, guiding the crew as they navigated a difficult bend in the river known as Coco Bend.

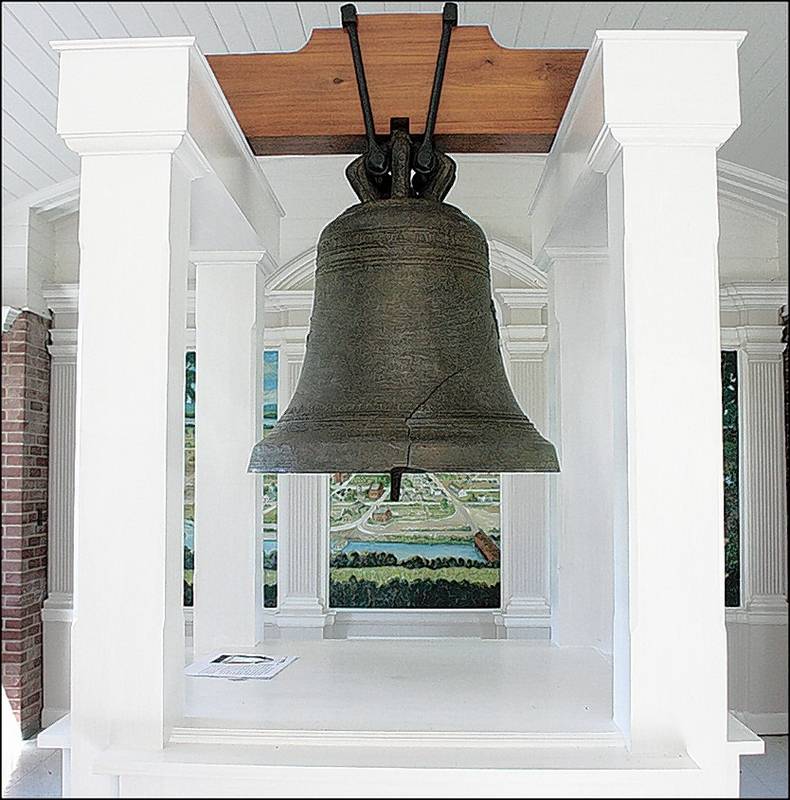

The original site of Kaskaskia remains in the state of Illinois even though it lies now on the west side of the Mississippi River. The small town features a magnificent old Catholic Church, interpretation concerning the Expedition’s visit, and the Liberty Bell of the West.

See the companion Illinois Side Inspiration Trip for things to see and do across the river in the town of Chester, the Pierre Menard Home, and historic Fort Kaskaskia.

Kaskaskia Bell State Historic Site (Liberty Bell of the West), 1st Street, Chester, IL, USA

4 mi

View Listing

Pierre Menard Home State Historic Site, Kaskaskia Street, Ellis Grove, IL, USA

5 mi

View Listing

Ste. Genevieve National Historic Park, the first established settlement west of the Mississippi River, stands as a testament to the rich French influence in early American history.

Visitors to the park can still see remnants of this French heritage, including the Bauvais-Amoureux House, a rare example of the poteaux-en-terre style of architecture, and the Jean-Baptiste Valle House, home to one of the first rose gardens west of the Mississippi. The Green Tree Tavern, open daily from dawn to dusk, offers a ranger-led tour of its historic structure, which once served as a home, business, and lodge.

On December 4, 1803, William Clark and the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed Ste. Genevieve during their journey up the Mississippi to find a winter home. Clark’s journal describes the town as a vibrant French Creole community, where French, Spanish, and African-American cultures coexisted.

Ste. Genevieve, MO 63670, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Sainte Genevieve Art Center & Art Museum, Merchant Street, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Sweet Things Sweet Shop, Market Street, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Knights of Columbus Jour de Fete, Market Street, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

European Entitlements, South Main Street, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Ste. Genevieve Welcome Center, South Main Street, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Ste. Geneviève National Historical Park, St Marys Rd, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

0 mi

View Listing

Ste. Genevieve - Modoc River Ferry, Little Rock Road, Ste. Genevieve, MO, USA

2 mi

View Listing

Explore Missouri’s rich lead mining history at Missouri Mines State Historic Site, located in the heart of the Old Lead Belt. The former powerhouse of the St. Joe Lead Co. now serves as a museum, showcasing historic mining machinery and one of the Midwest’s finest mineral collections. Discover how Missouri’s mineral wealth shaped its development—an interest dating back to President Thomas Jefferson’s instructions to Meriwether Lewis in 1803.

Missouri’s lead mining history dates back over 300 years, playing a crucial role in the state’s economic development. One of President Thomas Jefferson’s key objectives for the Lewis and Clark Expedition was to explore the Missouri River and assess its commercial potential, including the discovery of mineral resources. In his instructions to Meriwether Lewis on June 20, 1803, Jefferson emphasized the importance of documenting “the mineral productions of every kind: but more particularly metals, limestone, pit-coal, & saltpetre.” This directive aligned with the long-standing European interest in Missouri’s rich mineral deposits, particularly lead.

Although not a Lewis and Clark site, Mastodon State Historic Site is nevertheless an interesting stop on the way north to St. Louis. The site is the home of the Kimmswick Bone Bed, one of the most famous and extensive Pleistocene ice age deposits of fossils, including a number of bones of giant mastodons. Interpretative trails and picnic sites that dot the landscape and a museum that tells the natural and cultural story of the Clovis culture, which existed in the area between 10,000 and 14,000 years ago. Lewis and Clark separately visited and extracted specimens at a similar site in Kentucky called Big Bone Lick.

Jefferson Barracks, established in 1826 just south of St. Louis, Missouri, is the oldest continuously operating military installation west of the Mississippi River. Originally serving as the base for the first Infantry School of Practice, it was named in honor of President Thomas Jefferson. The post played a vital role in U.S. westward expansion, as well as in military operations during the Indian Wars and the Civil War.

The Sauk Indian military leader Black Hawk was imprisoned here after losing the war named for him in 1832. During the Civil War, Jefferson Barracks became home to one of the nation’s largest military hospitals, treating thousands of wounded soldiers. After the war, the post remained a key military site, supporting U.S. efforts in the Spanish-American War, both World Wars, and the Cold War. In 1960, the post was transferred to St. Louis County, which converted it into Jefferson Barracks County Park.

In addition to its military significance, Jefferson Barracks has a notable connection to Fort Belle Fontaine, a Lewis and Clark site. In 1904, the remains of soldiers and civilians from the abandoned fort were relocated to Jefferson Barracks.

Today, the site is home to the National Cemetery, the Missouri Civil War Museum, and several memorials. Over 200,000 veterans are buried here, including soldiers from the Civil War. It continues to serve as an active military installation, housing the Missouri Air National Guard and Army National Guard

St. Louis was founded as a planned village in 1764, designed to serve as a mercantile center for the fur trade. Pierre Laclède Liguest, a partner in Maxent, Laclède and Company, selected the site for its strategic location just below the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. In February of that year, his young lieutenant, Auguste Chouteau, led a group of workmen to lay out the village based on Laclède’s vision.

St. Louis quickly grew as French settlers from east-bank villages like Kaskaskia and Cahokia relocated to avoid British rule following France’s 1763 cession of lands east of the Mississippi to Britain. Although Spain officially governed Louisiana after 1770, the town retained its French character, language, and customs. In 1800, Spain secretly returned Louisiana to France, and in 1803, Napoleon, needing funds for his European wars, sold the territory to the United States in what became known as the Louisiana Purchase.

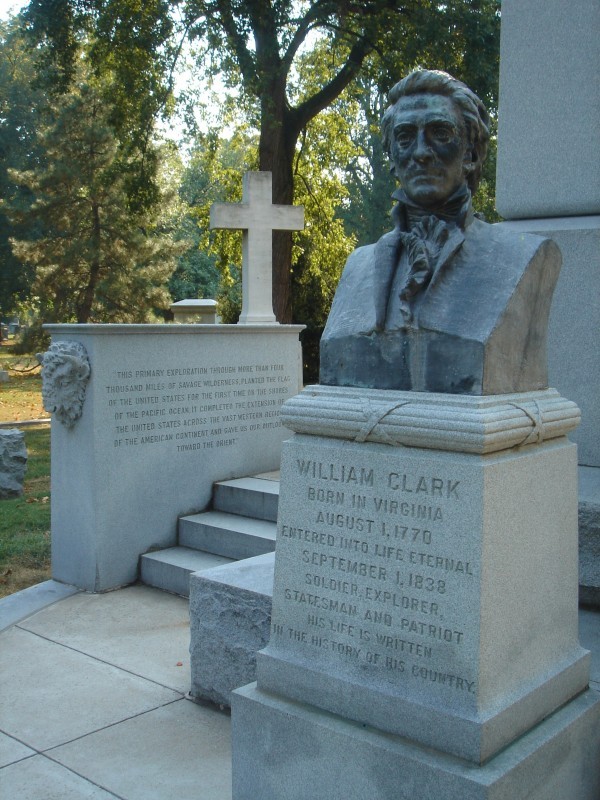

In March 1804, St. Louis formally became American territory. U.S. Army Captain Amos Stoddard oversaw the transfer, lowering the French flag and raising the U.S. flag over Government House. Meriwether Lewis, one of the leaders of the upcoming expedition, signed the Document of Transfer. Lewis had arrived in St. Louis in the winter of 1803, while his co-leader, William Clark, had first visited in 1797. Clark described the town as thriving, with stone houses, a small fort, and a bustling community steeped in French hospitality.

St. Louis’s location made it the perfect launching point for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which set out in May 1804 to explore the newly acquired western territory. The city’s role as a gateway to the West cemented its importance in American history, fulfilling Laclède’s vision of a great city on the Mississippi.

Additional Inspiration: Around St. Louis

Old Courthouse, North 4th Street, St. Louis, MO, USA

2 mi

View Listing

Bellefontaine Cemetery, West Florissant Avenue, St. Louis, MO, USA

5 mi

View Listing

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Sheridan Road, St. Louis, MO, USA

9 mi

View Listing

Lewis and Clark (Camp River Dubois) State Historic Site, Lewis and Clark Trail, Hartford, IL, USA

14 mi

View Listing

Edward "Ted" and Pat Jones-Confluence Point State Park, Riverlands Way, West Alton, MO, USA

15 mi

View Listing

Audubon Center at Riverlands, Riverlands Way, West Alton, MO, USA

18 mi

View Listing

Lewis & Clark Boat House and Museum, South Riverside Drive, Saint Charles, MO, USA

18 mi

View ListingOur bi-weekly newsletter provides news, history, and information for those interested in traveling along along the Lewis & Clark Trail.